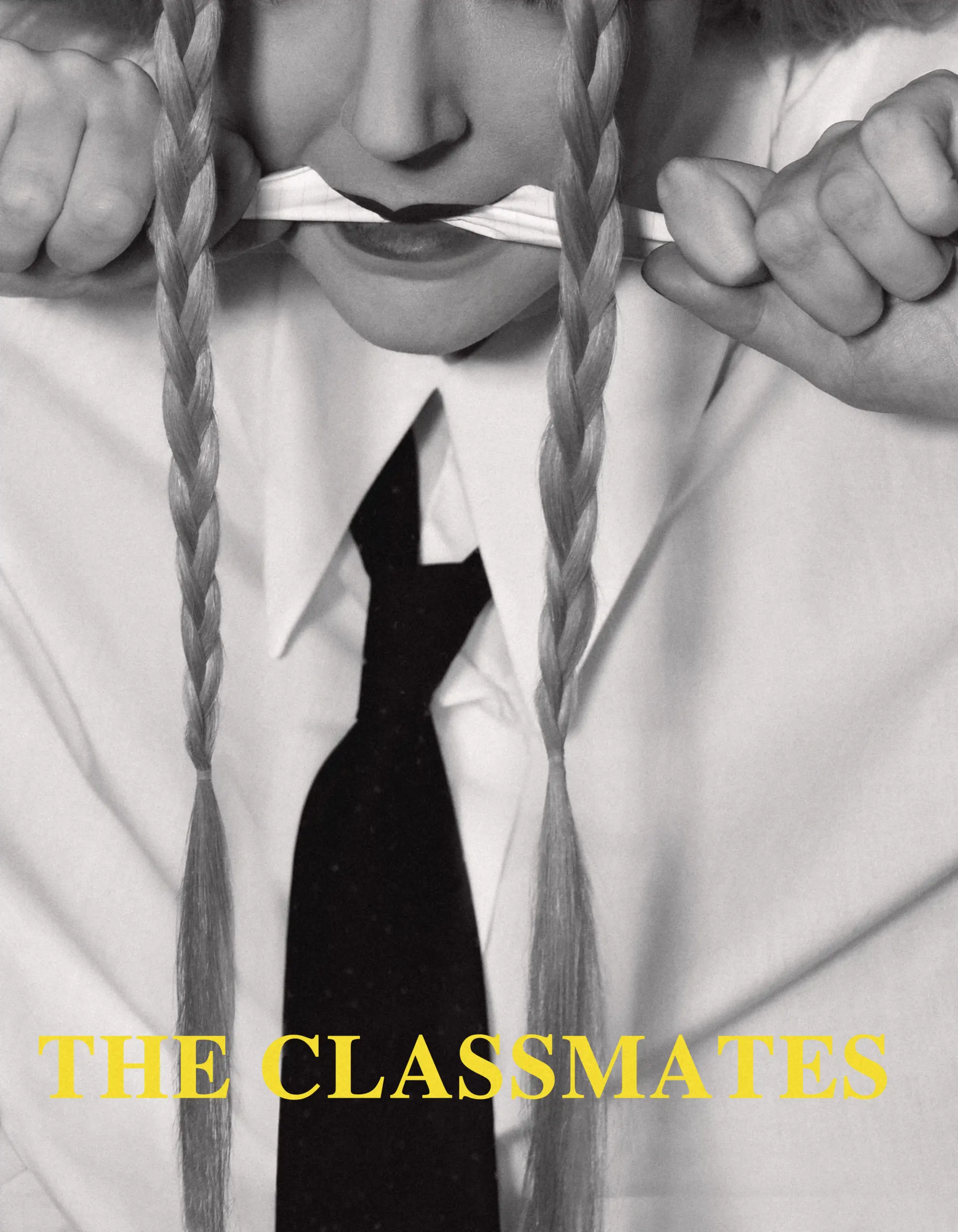

THE CLASSMATES

“The smartphone makes the world, it takes possession of it by creating it in the form of images,” writes the philosopher Byung-Chul Han about digital communication. Beyond the Truman Show, the system of hyper-productivity reduces the world to a product, and life to a spectacle; no distinction applies to the consumer machine, everything is potentially entertainment—even violence.

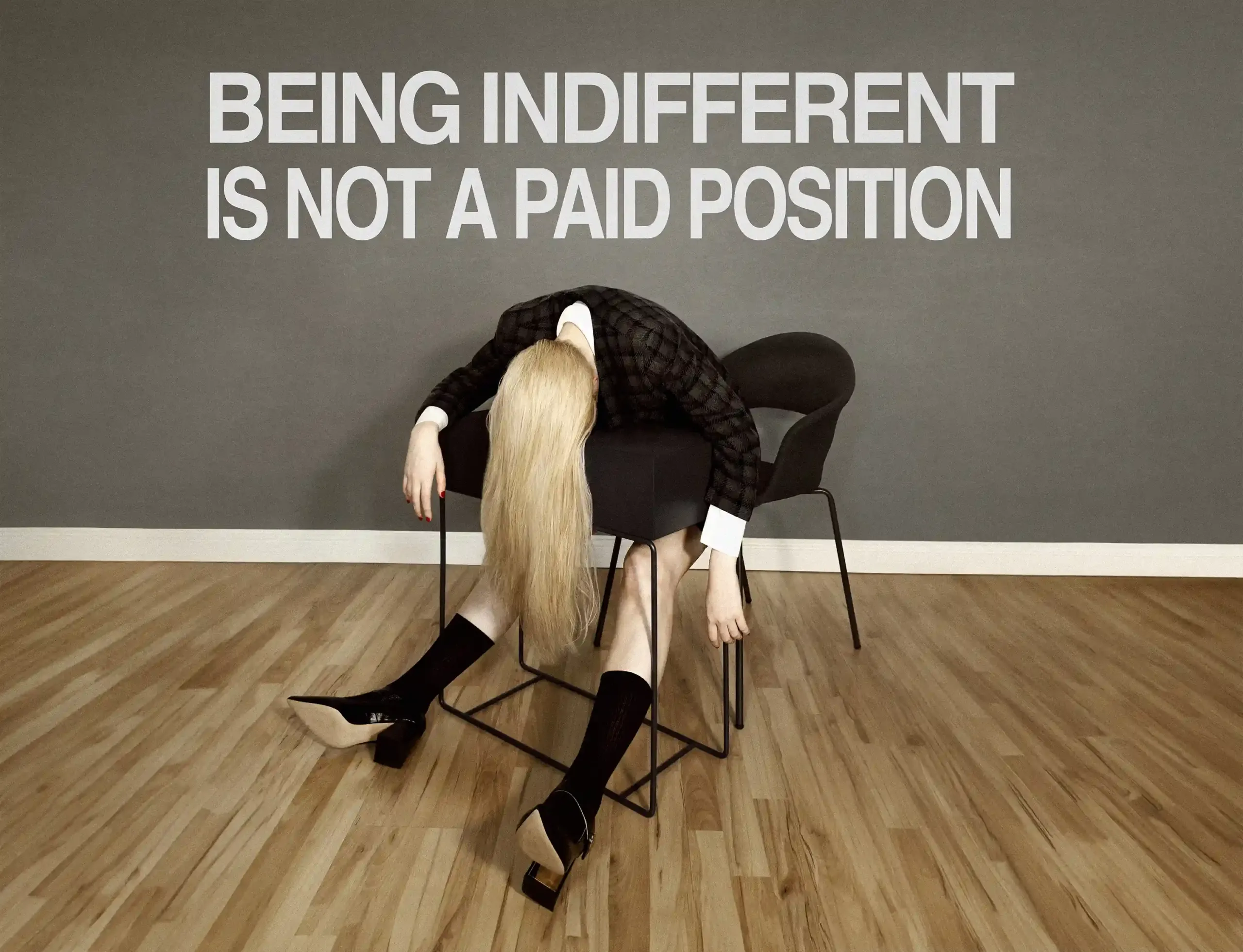

Think about the multiple news stories of abuse and aggression filmed and shared on social media, from the soldier dancing on TikTok after blowing up a neighborhood, to the gang slaughtering someone and bragging about the feat: the virtualization of experience legitimizes violence as it presupposes indifference (the abuse is filmed rather than stopped) and undermines its perception. Indeed, violence becomes a spectacle in the general anesthesia of the public.

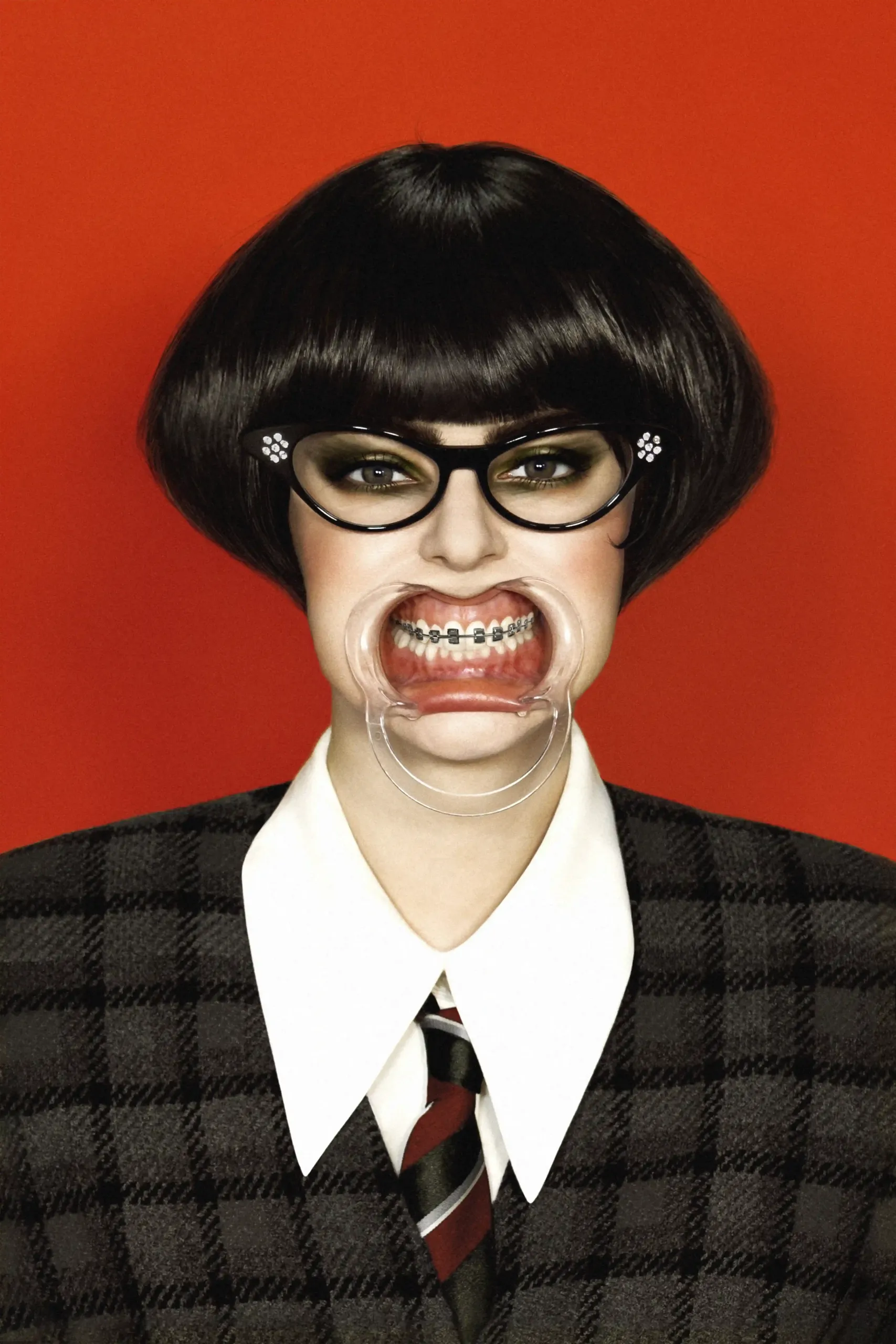

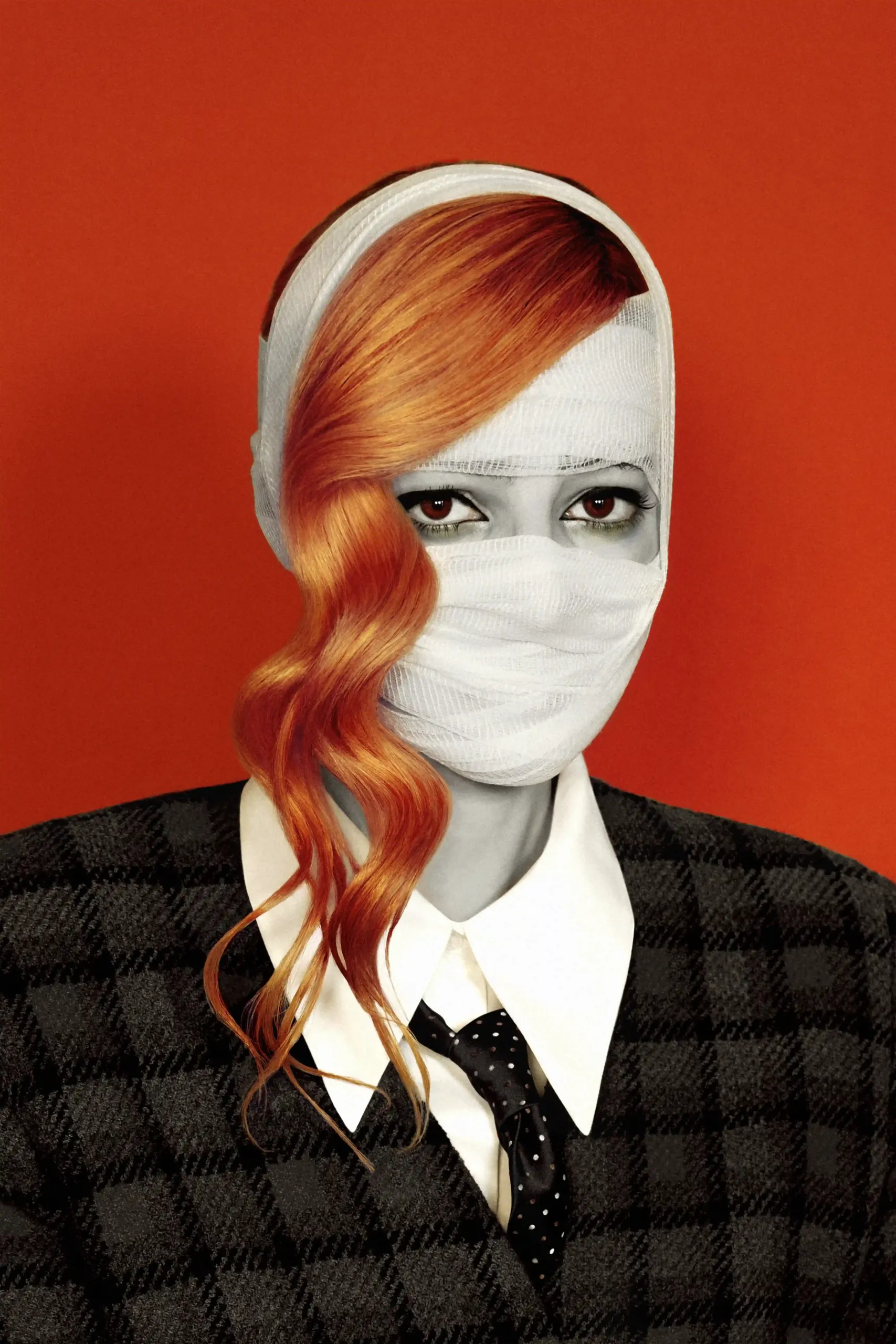

This is the framework in which the characters in The Classmates should be understood. Nameless students of an unknown institution, the only thing we know about them is the stereotype through which they are perceived and reduced by the dominant group: the peasant, the geek, the whore, for example, all stylistic features of an aggressive narrative. The portraits are thus the testimony of episodes of violence that have occurred and shared, the ruthless footage to feed the entertainment machine. The victim’s faces are displayed in an imaginary Wall of Shame, a public pillory that recalls the same brutal dynamic of spectacle as a cult. No saving figure glimpse on the horizon, not even the school, here an institution of equal black uniforms, reduced to a place of conformity training, far from the ideal place of formation and relationship building. Therefore, The Classmates is the staging of a power that knows no contrast.